Opinion: Marlon Moncrieffe on the Black British cycling community

It was in 2016 that I formally began my research into the lives of Black British cyclists. This was a personal journey of discovery, and there were many triggers for it. But most importantly for me, was to present alternative stories of cycling against the dominant white narratives of the sport.

As a former racing cyclist, born in London through parents and grandparents who had migrated from Jamaica, I wanted to know how racing cyclists that shared a similar heritage and identity to me were also ‘Made in Britain’.

Where was it in the country they grew up, and what was the impact of this for each of them getting involved cycling? What were their first cycling clubs and their experiences in these? Who were their mentors and coaches? Did they ever race for Great Britain? If so, what were their experiences?

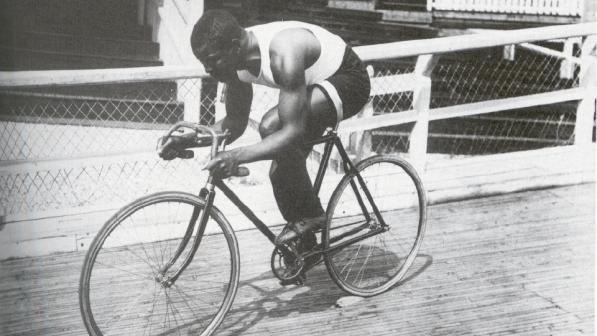

Early on in my racing career, I got to know more about Maurice Burton and Russell Williams, who both during the 1970s were seminal British champions for the Velo Club Londres based at Herne Hill Velodrome. I had read about the Northamptonshire-born road racer Mark McKay.

Later on, I came across the East Midlands road racer David Clarke, and the Manchester-born track sprinter Christian Lyte, and following this, the track racer Charlotte Cole-Hossain.

Shared experience

It was when I arranged to meet with each of the cyclists to get to know them better, and capture testimonies of their life and career experiences, that I began to make meaning of Black British experiences through the uniqueness of this collective memory. In my collation of this, I saw my advantage in being a Black racing cyclist, a Black thinker and Black writer in empathy, and in relating to their experiences.

One shared pattern, for example, was our entering dominant white spaces of power as the newbie Black rider and having to encounter white people who would (metaphorically) aim to strip down our cycling kit to expose the Black body we had brought in their white space.

Where from one viewpoint it may have felt as though you were being included, from another viewpoint you sensed that your Black presence was being ridiculed, othered and excluded by the narcissism of whiteness. Being forced to think about your skin colour as a difference in a white cultural space of power creates this double consciousness.

I translated the testimonies and featured these in my exhibitions of public engagement between 2018 and 2019 which I called Made in Britain: Uncovering the Life History of Black British Champions in Cycling.

In my book that followed, Desire Discrimination Determination – Black Champions in Cycling, I shared the lives, stories and cycling career experiences of seminal and more recent cycling champions emerging from the Windrush generation that became the Black British community of today, and from the likes of Clyde Rimple in the late 1950s, to Caelan Miller of more recent years.

My sharing is not just with a focus on road and track cycling, but also through the lives of the BMXer greats including Charlie Reynolds, the brothers Wayne and Gary Llewellyn, Winston Wright, Luli Adeyemo, Shanaze Reade, Quillan Isidore, Trevor Robinson, Tre Whyte and Kye Whyte and many more.

Black British BMX cyclists over the years have always had shoulders to stand on. But not so much with the disciplines of road and track cycling.

As a former bicycle courier in London during the late 1990s, I didn’t see many other Black cyclists. But I can recall there being two Black-led bicycling groups\shops in south London: De Ver Cycles in Streatham, and the Brixton Cycles Cooperative.

To a greater extent both were multi-ethnic groups, but symbolically the Brixton Cycles Cooperative, through its recognisable dreadlocked leader Lincoln Romain, seemed to me to want to celebrate Black cultural sensibilities in cycling. This also came through the design of the Brixton Cycles Cooperative kit which was based on the Afrocentric colours of red, gold and green, appealing to Black pride.

At the time, that bike shop was based on Coldharbour Lane, the heart of the Brixton’s Black community. A recreation of this Black symbolism in Black community cycling club attire has been trending in recent years.

When the Great British cycling revolution of this millennium in the early noughties hit its peak during the London Olympic Games of 2012, Black-led\Black-majority cycling groups began to emerge, particularly in London during and just after the Covid-19 lockdown periods of 2020-21.

New tribes

I share my observations of this in Chapter 12 of Desire Discrimination Determination – Black Champions in Cycling as ‘New Tribes In Cycling’, an intentional play on words against the norm of white-majority tribes of riders that I used to witness on the roads of London, Surrey, Kent and Sussex.

The new tribes I am talking about include the likes of the red, gold and green cladded Black Cyclists Network, BlackRidersAssociation, No Limit CC and Black Unity Bike Riders. Outside of London there is Team Raggamuffin of Suffolk and the Bristol Wheelerzzz Cycling Club. These do not form an exhaustive list of Black-led\Black-majority cycling groups.

Instagram as a social media platform of audio-visual communication was absent from the 1990s, but today this forum gives Black-led\Black-majority cycling groups the means to communicate an Afrocentric message, and appeal to congregate and ride in togetherness.

It is wonderful to see these cycling collectives from the Black community who simply love to ride together. I will be watching carefully over the next few years to see whether one or two or even a cluster of talented young Black British cyclists can emerge from these groups, to go on to represent Great Britain at the World Cycling Championships or the Olympic Games.

To what extent will their transition from red, gold and green, to red, white and blue be without the issues of race discrimination that many of the young talented Black British cyclists before them experienced?